how to cope when you're doomed by the narrative

a love letter to the chosen ones & the narratively screwed

Obviously—being who I am—I watched Thunderbolts* (The New Avengers). I walked into that half-empty theatre somewhat of a skeptic, walked out, tried to go on with my life—only to sheepishly, defeatedly, pull out my phone and type "AO3 thunderbolts" into the search bar, the way I do when a story mandibles into me and insists on a second life, a third, fourth.

Like you, I've been burned out on the surplus of lackluster Marvel movies and CGI horrors. I hardly expected Movie of the Year material from the new B-team band, with its unconventional star quality and lukewarm name recall. But on the car ride home from the theatre, I remember feeling like I’d touched, bafflingly, the quasar-hot pulse of something real. With the DCU properly kicking off its lineup of capes with none other than Superman at the helm in July, Supergirl next year, and—what I consider to be a spiritual cousin—the adaptation of The Legend of Zelda on the big screen (live action, groan) announced for early 2027, I think we're seeing what I always knew to be true, for better or worse: the massive appeal of the Big Damn Hero isn't going anywhere. At least not any time soon.

What is it about these narratives that captures our enduring affection? I've been sitting with this question as I prepare for MFA application season, cobbling together a project proposal I hope to spend a good few years with. I've been a sucker for these tropes since I was a chubby kid: The Destined Child, The Avatar, The Slayer, She Who Will Save Us All—but there's a specific class, a particular granular quality to the traditional hero that affects me like no other, inspiring the urge to eat drywall and block my mother.

You know the one: that character who smiles a little too forced, who leaves the function early to look for somewhere private to bleed. This hero's a little sour from the years. Costume's too big (not theirs). Cape like a noose (someone forced it on). Consider this entry an attempt—a love letter, if you will—for the chosen one, the special burdens of being loved by legend, and what they teach me about how to live in a burning world.

it’s dangerous to go alone, take this (you never had a choice)

In school, we studied John Locke’s seminal essay on human knowledge. In it, he argues that all individuals start as tabula rasa—literally translated, you are, from birth, a "blank slate.” You come to the world as void, as brand-new animal, blemish-free, without impulse or instinct. While I detested the idea, I couldn’t entirely deny its appeal.

After all, to be a blank slate is to be a state unencumbered by debts or obligations. Carrying over nothing from your ancestry. Owing no one. Imagine an existence where who you came from or where was something trivial, minor, satellite? Couldn’t be me lol.

The concept of human-being-as-clean-sock has been challenged several times over now, thanks to numerous studies on intergenerational trauma, epigenetics. A friend reminded me of the children of Holocaust survivors who dreamt of the very same nightmares their parents experienced, though they were never there. “Trauma demands repetition,” Selma Freiberg famously said. And while I didn’t have the language to explain myself then, stories showed me why.

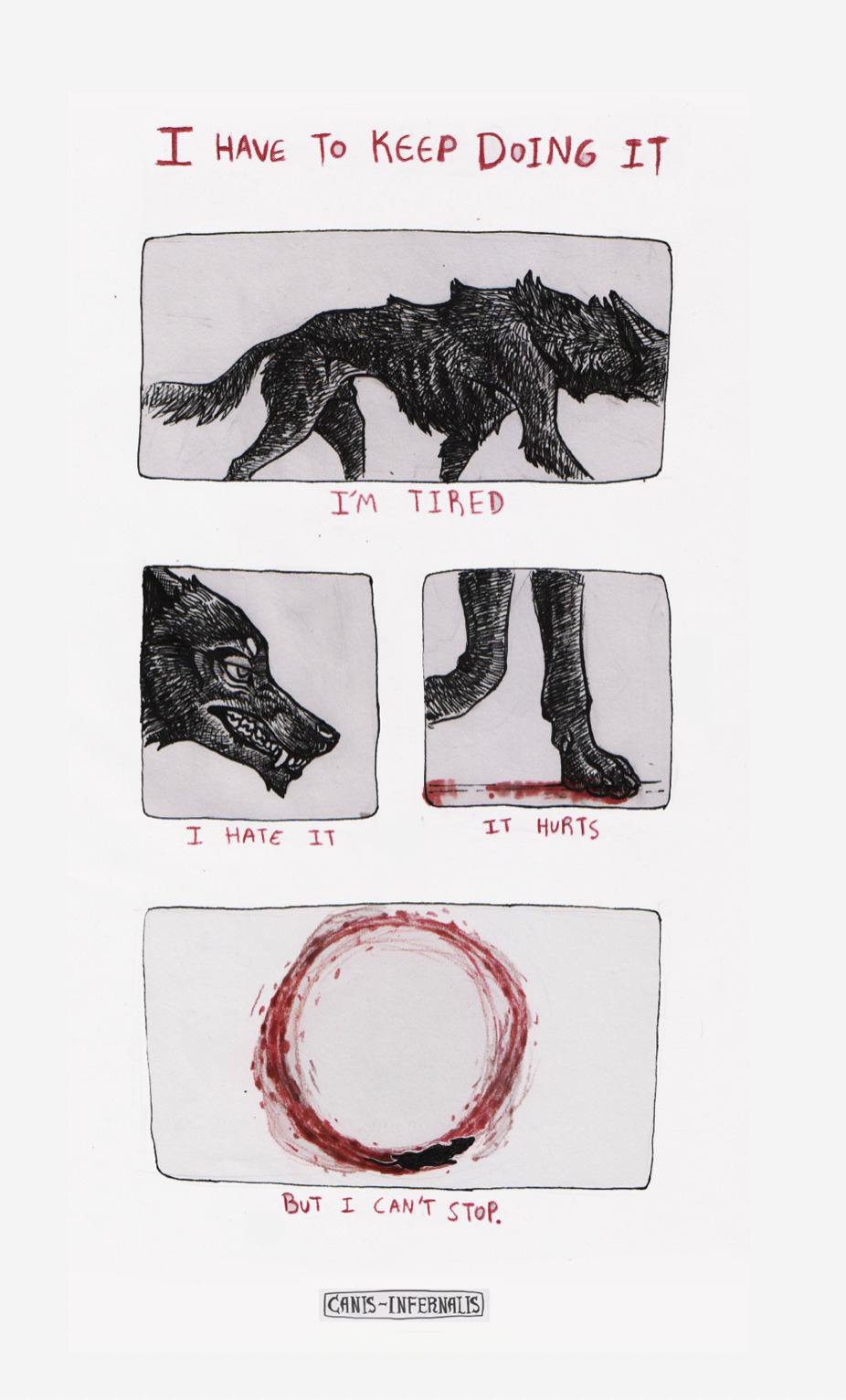

There is a hero archetype that directly confronts the notion of the blank slate. Often referred to as the Tragic Hero, The Martyr, the Shadow Hero, or just Doomed by the Narrative, their core trait is their repetition of cycles: violence, failure, loss, or resurrection. Maybe bonded by ancestral sin, cosmic punishment, or fate itself, they inherit a battle that began even before they were born.

If the traditional hero is valorized for their conquest, this hero’s tragedy is the opposite: their lack of freedom to choose. Sure, they’ll save the world—they have to.

Because their ancestors' war is their own. Because they thought the curse would skip their lineage in this lifetime, but they're already putting the chainmail on. Their mother's pain lightnings through their body. Their father's sword is in their hands.

I’m sure you’ve seen The Type in pop culture. If you need your memory jogged, allow me to share a few examples that I love, the shape of their stories marked by self-sacrifice, unfinished comings-of-age, loss of autonomy:

Yelena Belova and The Sister Cycle: Adrift, grieving, and haunted by Natasha’s legacy, Yelena walks out of the spy business and never looks back, only to—you guessed it—walk right back into the same team and mission that got her sister killed. While this return to form is meant to be read as a triumph, it’s the undercurrents of a superhero cycle unwillingly retraced that interest me.

Sam Winchester, the Boy-King: Young Sam always dreamed of escaping “the family business” for a regular life. He manages to leave for Stanford on a full ride, until his father’s disappearance pulls him right back where he started: blurring down the highway, pistol in his pocket. This is how Episode 1 starts. I mean, my guy was fed demon blood as a child by none other than a Prince of Hell and (spoiler alert??) destined to be Satan’s True Vessel. You can’t get more doomed than that.

Nightwing/Robin, the first child sidekick: Can you tell from the neon green shorts? The original boy wonder is a little different from the brooding man who raised him. But when Bruce Wayne goes missing, Dick goes through a literal and metaphorical “passing of the mantle”—moving back to Gotham, the stifling city of his childhood, and giving up the familiar blue Nightwing suit for the suffocating black cowl. So The Batman may live again, Dick Grayson had to die.

Link, or “Really, This Again?”: And what is this essay if I don’t talk about one of the most classic examples of the Doomed By the Mythic Cycle trope? Our legendary hero is named after a literal verb: Link, He Who Connects—obviously, us players to the console—but also the mortal and the divine, and time itself. Every Link of every game is the same, but not: the Hero of the Sky, of Time, of Wind, of the Wild—all descended from the same cursed hero, repeating the cycle of violence bestowed by the ancient evil king. Imagine meeting the guy who tried to kill you for the past 1,000 years as a stranger at the fruit market? Déjà vu must hit like crazy.

The questions these characters pose have no easy answers. When what makes you who you are is stitched inextricably to your predecessors, do you leave the seam in or cut it off and run free?

When what you inherit isn't something you choose, how do you keep carrying it?

Should you?

Why should it be you?

Why me?—that double-edged revelation that almost always catches our heroes by surprise. Almost immediately, they’re ambushed with shame. I know, because I’ve been fighting it for a long time too.

love, responsibility, and debts of the heart

I've always felt like I was born with built-in trauma. That sounds a little dramatic, but I mean it less in a woe-is-me eldest-daughter-angst kind of way, more in the knowing that I carry things in my head and my body that first belonged to someone else. I can hold a tune because my dad was a rockstar, and he filled our house with music—because his mom was a celebrated pianist, and she filled her house with music. I’m a terrible people pleaser (recovering!), and I think it’s because, above all things, I grew up fearing someone’s anger. My mom wielded it like a whip, the way my lola did, who was a scary ass housewife and believed disobedience was the fruit of all evil—something she learned from her father, a military man who died miserably in the Bataan Death March during the 40s. Or so I've been told.

I think I am drawn to—and relieved by—the idea of being part of a lineage predating all we know, a spring from which trickles both our gifts and our curses. Compared to the golden-haired heroes of old, the narrative shape of the doomed feels truer to my own experience as a queer Filipino woman—where often my life feels directed by forces I'm not privy too. Like growing up in a religious cult. Or being raised by a Beatles fan. Sometimes, I think my body remembers things it shouldn’t. And too often, I feel guilty for living a kinder life than my parents and grandparents did.

Which is to say: I am constantly freaked out by the catastrophic size of, as per Elaine Castillo, my utang-na-loob, those ridiculous, invisible, “absolutely unpayable debts of the heart.”

This indebtedness is rooted less in transactional relations, more in a deep, binding desire to sustain communal well-being, that Filipino idea of kapwa—the shared self. Our survival intrinsically linked. It’s a self-imposed debt, and impossible to quantify.

So when these characters ask: Will fulfilling my destiny consume me or make me who I need to be? I’m asking it too.

What if I can’t carry it any longer?

When will it be enough?

And: what if it didn’t have to be me?

And lately: what if these are the wrong questions?

what if it wasn’t a curse?

My generation came of age in a time of compounded crises. Witnessing genocide, ongoing pandemics, a worsening climate apocalypse, labor instability, and so on and so forth. It is getting harder and harder, I’m afraid, to release your inhibitions and feel the rain on your skin.

While the usual markers of adulthood begin to crack, I can’t help but feel that the future we were promised after years of study and #hustle is fading into a thing of fiction, myth.

The obvious solution was to rebel. In stories—and real life—I sought out themes of escape. Let’s band together and fight the powers that be, all the petty, unfeeling gods and goddesses who cursed us with this fate, and run off into a better future while AC/DC thunders in the background.

Your parents messed up? My therapist suggested no contact. The government letting you down? Leave the country! Burned out at work? Just zone out and focus on you, babe; repeat after me: self-care, brain rot, bullet journal, girl powerrr. Severance is the key. Severance is the only way out.

But every time a protagonist left their hometown, cut off their family, threw away their destiny to live in a beach hut somewhere while their hometown burned, not their problem, a part of me flinched. The idea that you could only find your Truest Self by rejecting your lot and burying the past felt violently alien to me. Maybe that’s just my savior’s complex talking. Maybe I’m still a people pleaser after all.

K-Ming Chang, author of the novel Bestiary, talks about inter-generational bonds in her interview with the San Francisco Writers Conference. “I was interested in a coming-of-age story that wasn’t about running away from the domestic space, but about burrowing and binding and rooting more deeply."

In Bestiary, three generations of women navigate their shared histories of violence, trauma, and love—but instead of growing more “individual” as they age, their voices begin to echo one another’s. Like a traveling wave that returns to the ocean from whence it came. By retracing each other’s paths, they enter into a deeper kind of knowing. And only then are they able to grieve, heal, and forgive.

In this same way, I am becoming more and more interested in the question: What if the destiny you inherited doesn’t have to be a curse?

There is no erasing or forgetting the past. And there is sure as hell no erasing future hardship. But what if it can be eased, if only a little, with the tools we were given? Namely, the knowledge that we weren’t the first—someone did this before—and that the curse cannot be lifted by escaping into our independent paper silos of ham-fisted will and determination?

What if we could take the narratively fucked—and make it new?

heroes as cursebreakers

I can't talk about Marvel’s Thunderbolts* without spoilers (it is May 2025 as of this writing), so let's talk about The Legend of Zelda instead. Here’s a popular fan take: fate can be broken. Even vessels of the gods can defy the divine and pave the lives of their choosing. But for some reason, I am infinitely more touched by the way the fan animated series Hero’s Purpose portrays this destiny: not as a burden to be broken free of, but a burden to be shared.

In its penultimate scene, Link mirrors Demise’s pose when he first doomed him to the eternal curse (after absolutely rocking his shit, btw, drawing every power move from all his past lives). Lifting a defiant finger, Link announces, “I am to you what you are to me. I will never stop fighting you. I will chase you to the ends of the earth. To the ends of time itself."

It’s an unforgettable narrative-shifting moment. The power shifts. Or rather: it rights itself. No longer is Link The Cursed One, burdened by affliction unending—for by braiding his voice with the multiplicity of previous heroes, he changes to become this equal power as well! The very thing that doomed him becomes the one that saves, the blade itself!

It’s a story that insists: the real coming-of-age is a coming into plurality. And this communal burden does not negate the cost, but lightens it, transforms it.

This is the narrative shape I think our hero stories will always need. Maybe not as literally as Link’s—but one shaped by acknowledging our indebtedness to one another. This starts not by denying our past, but by sitting with it, reading it, understanding it, so we may break the cycles that demand breaking.

Maybe we can’t choose what we inherit, but we can choose what we pass down.

In a prelapsarian earth, it would’ve been cool to have agency over the villains of our lives. But again I return to Audre Lorde’s wisdom: “Sometimes we are blessed with being able to choose the time, and the arena, and the manner of our revolution, but more usually we must do battle where we are standing.”

So here’s to the chosen ones—for holding up the mirror to the patterns of our lives. For teaching me how to persist through trauma, loss, and rage, and still return to hope. Thinking now of all the rooms that led to me being here: the lonely offices in Hong Kong where my dad spent as an OFW; the laps of my cousins who looked after me as a child; the love stories of my grandparents so thrilling, I’m confident no man or woman will ever hurt me in any novel way. It is a relief to know I’m not the first nor the last of my kind. That I will never have all the answers. And to my ancestors, both living and dead—one day I hope I can forgive you. I’m glad I’m not alone. Haunt me, okay? Haunt me!

DIVA!!!!!